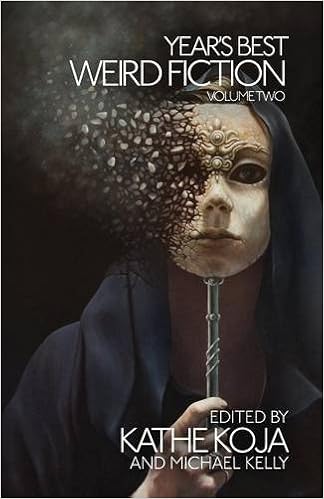

Undertow Publication’s Year’s Best Weird Fiction series reaches its second volume, this time guest-edited by Kathe Koja alongside Michael Kelly. In comparison to the first volume (which I reviewed here), there are less stories this time that draw from the horror tradition of Lovecraft, Aickman, Ligotti & the like, and more dark fantasy. Whereas my memory of the first book is, perhaps erroneously, of stories of people isolated and alone, the stories here seem more concerned with the relationships between characters as a source of weirdness, whether those relationships be familial, romantic, civic, or more ambiguous. There seems to be more focus, too, on linguistic experiment and playfulness–exemplified by the two stories included by Carmen Maria Machado, once of which has the fantastic title Observations About Eggs From the Man Sitting Next to Me on a Flight from Chicago, Illinois to Cedar Rapids, Iowa. And it does exactly what it says on the tin.

There are twenty stories here, and as always each reader will likely have their favourites. Here are mine, with a few brief words why.

Wendigo Nights by Siobhan Carroll – the wendigo has, of course, been part of horror fiction dating back to at least Algernon Blackwood’s tale, but this story finds a new angle on it, featuring not an external creature (probably) but the internalised idea of ‘wendigo psychosis’. Centred around an stranded team of scientists at an Arctic research camp, it also owes something to The Thing's creeping paranoia. No bad thing.

Headache by Julio Cortázar–not, of course, a new story, but one newly translated. And what a joy it is to read a ‘new’ Cortázar story; whilst maybe not quite up there with something like House Taken Over, Headache still has that characteristic aura of matter-of-fact strangeness. It tells of a group of people looking after creatures known as ‘mancuspias’, the exact nature of which is deliberately hard to visualise for the reader. The creatures’ keepers do not seem to know exactly what they are doing (or why) and as conditions deteriorate they increasing suffer from ailments like vertigo and migraines…

Nanny Anne and the Christmas Story by Karen Joy Fowler–a nanny tells the children in her charge a story, which may or may not have some relevance to their life. A story with an ambiguous, skilful blurring of what is real and what isn’t, and which plays on all sorts of childhood fears.

The Air We Breathe Is Stormy, Stormy by Rich Larson–a story similar in tone to some of the more horror themed material from Volume 1, the central character here is a man fleeing society and his responsibilities to work on an oil rig. There’s a mounting sense of tension as he thinks he sees someone or something in the dark and stormy waters, before an unforeseen emotional pressure change at the climax.

The Husband Stitch by Carmen Maria Machado–the other story by Machado might have the better title, but it doesn’t have the narrative and emotional punch of this one. A story of a woman’s sexual awakening and marriage, the weird element here only subtly intrudes, and the full, horrifying significance of it is only revealed towards the end.

Resurrection Points by Usman T. Malik–a story which uses the weird to explore political and religious conflict, Resurrection Points is centred on a young boy in Karachi with a miraculous power both to heal and make dead bodies move. As his sense of power grows so does the conflict and violence around him; the two strands of the allegory intertwine and together create a dramatic and disturbing climax.

Exit Through the Gift Shop by Nick Mamatas–a second-person post-modern riff of on the horror campfire tales of ghostly hitchhikers, this generates laughs as much as unease. At least for awhile... Clever, playful, and with some of the most horrific imagery in the anthology: a combination that shouldn’t work but in Mamatas’s hands really does.

Migration by Karin Tidbeck–the weird is a self-contained world (or series of worlds) in Tidbeck's fascinating story where the inhabitants of a settlement that exists only as a vast staircase are forced to move to every weirder dwelling places.

As my selection above hints at, one of the highlights of Year’s Best Weird Fiction 2 is the range of authors it includes in its comprehensive and generous definition of ‘the weird’. There are new names and old faces; horror, science-fiction and fantasy; works in translation, an almost equal representation of women as men, and writers from a wider variety of countries than in most of anthologies. There’s even stories by writers a few years dead alongside those living, which is another kind of diversity I guess…

Both volumes of Best Weird Fiction come highly recommended by this reader, then, and it will be interesting to see where Undertow take the series with the third volume.